On September 21, Social Science Matrix was honored to co-sponsor a virtual Matrix Distinguished Lecture by Katharina Pistor, Edwin B. Parker Professor of Comparative Law at Columbia University and Director of the Center on Global Legal Transformation.

In her lecture, Pistor discussed her book, The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality, which argues that the law selectively “codes” certain assets, endowing them with the capacity to protect and produce private wealth. The book was lauded as one of the Financial Times‘ Best Books of 2019 in the field of economics and one of the Financial Times‘ Readers’ Best Books of 2019.

The event was co-sponsored by the Berkeley Network for a New Political Economy and introduced by Steven K. Vogel, Chair of the Political Economy Program, the Il Han New Professor of Asian Studies, and a Professor of Political Science at UC Berkeley.

“One of the core questions that the book addresses is the question of, what is capital?” Pistor explained. “What I’m basically arguing in the book is that capital is a wealth-generating asset. And what we have to understand is the legal DNA, if you want to call it that, or the ‘code of capital.’ We have to understand what kinds of features create assets that are really wealth-generating.”

As an example, Pistor noted how a piece of land is only considered to be “capital” when it is classified as such by the law. “If you take land, it’s just a piece of dirt,” she said. “If you want to monetize land, you have to graft certain legal protections for the holder of land rights onto that land. That’s not natural. It’s a social decision. One of the critical questions is, who makes this decision on behalf of whom, and who has access to or control over the decision-makers? Let me just take away the punch line: lawyers are really important here, including private transactional lawyers who work mostly in private offices behind closed doors.”

Pistor explained that different legal frameworks work together to “code” capital, including property law, trust and corporate law, bankruptcy law, and contract law. She said that all capital has certain shared characteristics, including priority, with the law determining who has rights to assets, with some rights stronger than others; and durability, the ability “to extend rights that we bestow on asset holders over time and to protect these rights from too many other competing claimants.”

Another defining attribute of capital, Pistor said, is universality, which ensures that the priority and durability rights are protected not only between two people who entered into transaction with one another, but are “actually enforced against the world,” Pistor said. “The state comes in here because it will enforce these titles, not only against parties to the transaction, but against anybody” Another defining trait is convertibility, the ability to convert assets into other assets, such as cash. “Three out of those four, and then you have something that I would call capital,” Pistor said.

Pistor emphasized that the subtitle of her book, “How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality,” relates to how the law is “a representation of the centralized means of coercion… As lay people, we may think of law as a relationship between the citizen and the state by which the state governs its citizens. And we might also think about civil and political rights, or human rights more generally, and realize that actually, citizens can also use the law, which is a creature of the state, against the state itself, in order to protect their own individual, civil, and political rights. And then there’s this third dimension, which is really what my book is all about, which is that citizens can harness the centralized means of coercion of the state for their own means when they want to organize their relationship with other citizens. It is this horizontal relationship between citizens — or actors that don’t have to be citizens — who want to harness the law to avail themselves of the coercive powers of the state to organize their private rights.”

The beauty of digital code is that it is highly scalable. We don’t even have to rely on a centralized state power at the territorial nation-state level, but we can create digital relations across national boundaries.

Pistor drew upon legal history to explain how, starting with land, the same “core modules” have been used “time and again” to code capital. “We can see a lot of capital creation and a lot of also skill development for how to code capital,” she said. “Once lawyers and their clients understood the mechanism, they realized that the same legal coding techniques could be applied to different types of assets.”

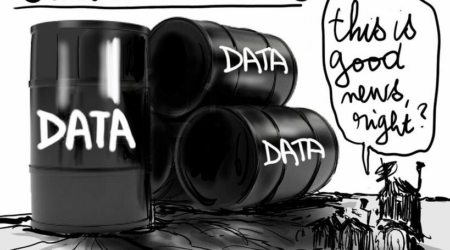

“One of the questions I asked myself in the towards the end of the book is whether the legal code might be replaced at some point or is already being replaced by the digital code,” Pistor said. “The beauty of digital code is that it is highly scalable. We don’t even have to rely on a centralized state power at the territorial nation-state level, but we can create digital relations across national boundaries. In the book, I come out with the question, is this a new kind of code, and will it replace the legal code? Or is it more complementary, where the legal code will encode the digital code, rather than the other way around? I think that question is still open.”

Pistor argued that the processes through which capital is “coded” through legal mechanisms need to be reformed to reduce wealth inequality. “We have to get at the system,” Pistor said. “It’s not enough to chop off a head of a ruler, what you really have to do is get at the system. The system, of course, is resistant. So you have to use an approach I call “strategic incrementalism….” It’s basically taking a page out of the script that lawyers and capital holders have used over centuries to say, okay, how did you do this, and what did you need to accomplish this? And how much do we have to take back to so that we can make sure that we can cherish our democratic values and get the upper hand in governance again?”

Watch the lecture and Q&A above or on YouTube.